| UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA - AFRICAN STUDIES CENTER |

NEWS AND DEVELOPMENTS

Extension of UNMEE Mandate

In order to maintain critical support for the peace process in Ethiopia and Eritrea, the UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan recommended a six-month extension of the mandate of the peacekeeping mission now deployed in both countries. If the Security Council agrees to the proposal, the UN Mission in Ethiopia and Eritrea (UNMEE) will be extended until 15 September. In his report to the Security Council, the Secretary-General noted progress made in the peace process and as well as obstacles to the establishment of the proposed Temporary Security Zone (TSZ) between countries. The Security Council is scheduled to discuss the report in consultations on 13 March, which the Secretary-General's Special Representative, Legwaila Joseph Legwaila, will attend, will attend.

RONCO to Train Civilian Deminers

A four-member team from RONCO Consulting Corporation, an international professional services firm that provides advisory, training, implementation and management assistance in the field of demining, visited Ethiopia in early March to plan for the training and retraining of up to 200 civilian deminers in Addis Ababa together with the Ethiopian Mine Action Office. Funded by the U.S. Department of State, this training program, planned to coincide with the arrival of equipment, is scheduled to begin in May. Training will focus on manual demining, using metal detectors and ground prodding techniques. RONCO was previously in Ethiopia in 1995 to train military deminers.

Afar Isolated from Water Point

It has been reported that Ethiopian Afar herdsmen may not have access to the LIMOSIN water point in Northern Afar located within the temporary security zone (TSZ). UNMEE and the UN Resident and Humanitarian Coordinator in Ethiopia are looking into provisional actions.

Passport for Livestock

During a mission to Djibouti undertaken in February by the FAO Emergency Coordinator for the Horn of Africa, the Djiboutian Authorities raised the issue of a better livestock health certification mechanism at the port. They think that such improved facilities would facilitate the livestock trade from the Horn of Africa by restoring a better level of confidence on the safety of exported livestock. However, as the majority of animals exported are from neighboring countries, they expressed their concern to see the on-going regional initiative to be speeded up in order to complement the national programs.

Steps Taken for a Future Lift of the Livestock Ban on the Horn of Africa

A visit to Somalia, Ethiopia and Sudan by a four-man team of veterinarians from the United Arab Emirates (UAE) is considered a step forward in attempts to reopen the livestock market following a Rift Valley Fever ban imposed by the Gulf States. This project was funded by the European Union and sponsored by FAO. The aim of the visit was to review the health situation of livestock and the condition of processed meat in Somalia. The team wanted to ascertain whether Somali livestock were free from RVF. The BBC reported that the experts announced that the livestock of the Horn of Africa, especially Somalia, were free of the Rift Valley Fever and also said they were impressed by the health of Somali livestock. The lift of the ban however, remains at the discretion of the countries that imposed the ban.

WFP Jijiga is also reporting that merchants are already buying up livestock again in anticipation of the livestock ban on the Horn of Africa being lifted.

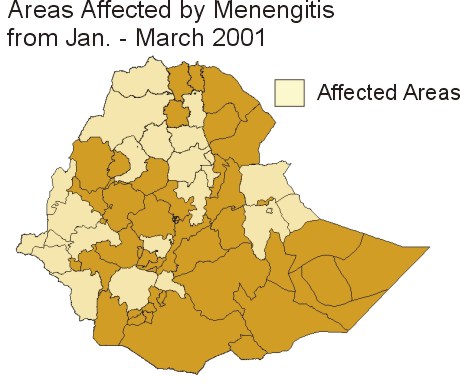

WHO: Meningitis Outbreak Intensifying

Reports reaching WHO Ethiopia confirm that another cycle of sporadic meningococcal meningitis outbreaks in the country, which began late last year, has intensified during the first quarter of 2001. Between October 2000 and 1 March 2001, a total of 1,900 cases and 141 deaths were reported from 59 districts (weredas) in 21 zones, involving 9 of the 11 regions in Ethiopia. The level of the epidemic is a serious concern, if not for numbers, for the geographical extension of the outbreak.

The sero group identified in almost all areas is sero-type A, the most virulent strain of meningitis and the main cause of major epidemics. The age group most affected is under 30 years (80%).

In late February, the Ministry of Health (MoH), issued an appeal for "Rapid Intervention in the Control of Meningococcal Meningitis Epidemic in Ethiopia" and emphasized that more than 8.4 million people are at risk. To support the appeal of the Ministry of Health, various actions have been undertaken in the regions and districts throughout Ethiopia. To coordinate the intervention effort, a team of interested partners is working with government both at federal and regional levels. Partners have been requested to supply vaccines and syringes as per the preparedness and response plan submitted by the government. In those zones reaching epidemic levels, vaccination campaigns have been pursued or are ongoing. Other zones are under surveillance. UNICEF, WHO, MSF-Belgium, MSF-Holland and other NGOs, working in close consultation with and under the overall coordination of the Ministry of Health, continue to monitor the situation closely.

Thus far, 766,000 doses of vaccine have been received in country (UNICEF 500,000, MSF-H 66,000, IFRC 200,000), in addition to the strategic stocks of 425,000 doses already pre-positioned from last year (WHO 200,000, MoH 150,000, UNICEF 75,000). With a total of over 8 million vaccines needed, and pledges of some 3.3 million doses, there is a shortfall of 3.9 million doses of vaccine. To combat this defict, UNICEF is now considering the procurement of additional vaccines while WHO is procuring 10,000 doses and has submitted proposals through WHO/HQ to ECHO and OFDA.

The MoH reports that in general large epidemics of meningitis should be expected every eight to twelve years. Since the last large epidemic occurred in 1989, the next cycle could be expected between 1997 and 2001. The MoH also noted that meningitis repeatedly occurs during the dry season between late January and May.

PFE to Launch a National Conference

on Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper

Pastoralist Forum Ethiopia (PFE) was established in 1998 as the only civic institution for pastoral advocacy in the country. With the main objective of enhancing pastoral development, it is now serving as an umbrella organization open to all organizations and individuals working on pastoral development. A number of NGOs are already participating as members in this organization. The United Nations Emergencies Unit for Ethiopia (UN-EUE) is the latest addition to the list.

PFE’s main areas of activities include networking at national and international level, commissioning policy oriented research, facilitating the opening of a pastoral centre for documentation and information, organizing briefings, workshops and annual conference at the national level. All activities are coordinated by Panos Ethiopia, a local NGO.

The Forum organized its first national conference last year and currently is preparing for a second which will focus on the reflection of pastoral priorities in the Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper (PRSP) now under discussion.

A New Structure for IDPs?

In a meeting with the Ethiopia UN Country Team (UNCT), Ms. Gawaher Atif, who arrived in Ethiopia on 12 March for a four-day mission to Ethiopia, fielded pointed questions from Heads of UN Agencies on the latest UN efforts to find workable solutions for internally displaced persons (IDPs) worldwide. Ms Atif, Liaison Officer in the WFP Geneva Office, is in Addis to follow-up on the recommendations made by Dennis McNamara and the mission of the Senior Inter-Agency Network on Internal Displacement who visited Ethiopia in October last year.

Currently no UN agency is specifically mandated to handle IDPs and the UNCT expressed concern that a new structure might be formed to respond to IDP concerns. Although the Senior Inter-Agency Network on Internal Displacement has not yet made any recommendations, Mr. McNamara in his earlier visit intimated that it was not the intention of the Network to create another agency and that an inter-agency body that would act as a catalyst and empower UN Country Teams in their respective operational theaters was more the aim of their efforts. The Network plans to prepare a preliminary report in March and will follow with the issuance of a final report in May.

During her visit, Ms Atif is meeting with the DPPC, UNCT, ICRC and IFRC and selected NGOs. Ms. Atif will report to the UN Special Coordinator on Internal Displacement (UNSCID) and will undertake a follow-up of the status of implementation of Network mission recommendations for each country visited by the Network. The follow-up review will be carried out in close collaboration with RC/HC and the UN Country Teams. She will also brief the UN Special Coordinator on the results of the follow-up.

A Well-Developed Belg System Established over the Country

(courtesy of FEWS)

The much anticipated belg rains began in central parts of Ethiopia toward the end of February and early March. While rains that started in early February were poorly distributed, national climate forecasters predict that the rainfall regime will strengthen through March and continue through April.

By the first week of March a well-developed belg system had become established over the country, producing rains in the belg areas of South Tigray and North and South Wello, Oromiya and North Shewa Zones; central and southern crop-dependent areas were also receiving very good rains. In the southeastern livestock dependent areas rains have just started, marking an early onset of the rainy season.

Belg farmers in many locations are sowing long-cycle cereals, such as maize and sorghum, through the first half of March. Barley is currently being sown in the northern highlands. Depending on the location, sowing will continue until the start of the meher season in June. As rainfall becomes more widely distributed, moving from south to north, farmers will also plant short-cycle crops, like teff.

OPERATIONAL ACTIVITIES

Mission Undertaken to Review

UNICEF-Supported Mine Awareness Activities

From 3 to 5 March, senior UNICEF Mine Action and Emergency staff reviewed the technical status of UNICEF-supported mine awareness activities in Tigray region, implemented through the national NGO, RaDO with local government and community participation. The mission included UNICEF’s Global Landmines Coordinator from EMOPS New York, the UNICEF Mine Awareness Technical Advisor, UNICEF Ethiopia and Eritrea Emergency Officers and was joined by Mekele-based UNICEF and WFP staff. The team met with the head of Regional DPPB, observed community-based mine awareness activities in Guersenay, Afherom Woreda including woreda and tabia mine agents and spoke with displaced families unable to return to home villages due to mine contamination.

On 8 March, the second joint RaDO/UNICEF data report on mine/UXO incidents in Tigray zone was released, including data for 1998 and 1999.

WHO Supports IDPs in Eastern Zone of Tigray and Afar

Rehabilitation of the Health System in War-affected Areas

WHO has begun the rehabilitation of heath facilities in war-affected zones of Tigray Regional and Afar State. In February 2001, the rehabilitation of six health posts, five in Tigray and one in Afar was initiated. The construction, equipping and furnishing of these health posts, supported by the Government of Norway, is expected to be completed within eight months. The zonal referral hospital at Adigrat will be strengthened to give referral and mobile support to surrounding weredas.

Refresher Training Courses PlannedWith the health staff in these health posts having left during the war, the gap created is planned to be closed, first by locating these frontline health workers and then by giving them in-service training. A new training programme will be organized to meet these shortages. The Adigrat Hospital and Axum Nursing School will be responsible for the training. WHO has assigned a health specialist to assist in the preparation and implementation of the training programme as well as in the physical rehabilitation of the health facilities. The refresher/in-service training courses for Frontline Health Workers - Primary Health Workers, Junior Mid Wives and village Health workers, Community Health Agents (CHAs) and Trained Birthing Attendents (TBAs) is being developed to meet the current need and is expected to train a total of 70 frontline health workers and over 100 junior clinical nurses.

OR and X-Ray Facillities Improved to Help Landmine Victims

In order to improve the capacity of the Zonal Referral Hospital at Adigrat, with a 120-bed capacity, to handle landmine victims and other critical injuries, WHO is working with the Regional Health Bureau (RHB) to improve the OR and the x-ray facilities. The Hospital is being strengthened with the establishment of a landmine surveillance system.

Regional Authorities Indicate Poor Achievement Towards Supporting IDPs

In February 2001, WHO undertook a visit to Tigray Regional State. Regional authorities indicated that not much has been achieved towards supporting the IDPs. As a follow up to the appeal 2001 and the concern of the regional states, WHO contacted several embassies and donors and requested a review of the 2001 appeal and to support the process. WHO also arranged a meeting between the DPPC, some donors and WHO officials on the non-food requirements both for IDPs and drought victims and created a forum for their concerns.

RELIEF FOOD AND PLEDGES

A new WFP Emergency Operation (EMOP) is expected to be approved shortly,for approximately 200,000 metric tons, to cover the needs of 2.5 million people for ten months.

SPECIAL REPORTS

One on One with Bronek Szynalski,

Regional Humanitarian Coordinator for the Horn of Africa

Question: The majority of the humanitarian community now considers the crisis over. Therefore, what is the major role of the Regional Humanitarian Coordinator?

Answer: Well, the crisis is not over! The crisis will only be over when people have regained their livelihoods and we are at least reasonably secure that they can face another crisis with some confidence. At the moment, that certainly is not so. We are still talking about more than 12 million people at risk, in the Horn of Africa, and all of them need assistance for part of this year, including food.

Question: What is the one most important issue that the office of the Regional Humanitarian Coordinator is handling now?

Answer: I would say that the most important issue is to continue mobilizing resources and the response so far has not been too good because donors think that the crisis is over. The public, and donors, look at what is evident, visible. If they see people badly malnourished, then they will respond. We have managed to address the issue of potential or possible famine, but people have not recovered. And we have to convince donors that the crisis is still on and will not be over until rains come, new harvest is in, and reserves are built up for another crisis. Therefore, our major role will be in the field of advocacy and the mobilization of resources. In this case we are talking about mobilizing non-food inputs for rehabilitation and recovery, as well as considerable quantities of food aid.

Question: Can you highlight some of the other main issues that concern your office?

Answer: I will start with security, in certain areas of the Horn countries, as well as across borders: As we all know from reading the papers, between Kenya and Ethiopia, between Somalia and Ethiopia, there are continuous security incidents and therefore delivery of assistance is either not possible or severely constrained. Until we can guarantee security, normal assistance, and even more recovery, will not be possible. That is one of the major issues that the regional humanitarian office needs to address, together with the Security officers in the UN Offices across the Horn. Secondly, the economic sector that is of great concern to us is the pastoralist issue and that of livestock herders who have been first to be hit by the crisis last year. And, we know that they have long outstanding and long-term problems. These have to be addressed and we want to ensure that something is done to reflect on the challenges facing the pastoralists economy in this age and time. These are simple folk, attached to their traditional way of life; they move around and no government in the area has found a solution with regard to how to address their needs simply because they’re such a difficult group of people. We are trying to get donors support to develop programmes that will analyse these needs, at community level, have them seriously considered at regional and central government level, and eventually develop strategies that would provide a long term solution to their precarious existence.

Question: What about Rift Valley Fever?

Answer: One of the very practical problems that have been faced by the pastoralists relates to Rift Valley Fever. This has affected, in a pretty dramatic way, the livestock herders in Somalia, in Ethiopia, even in Djibouti and Eritrea, as well as to a lesser extent perhaps those in Kenya. There is a good deal of movement between countries; therefore, it is a problem that affects everyone. It affects livelihoods and it affects the future. There is no point in rebuilding herds that have been destroyed, diminished in the drought of the year 2000, if there is nowhere that livestock can be sold. Much of the production in some of the Horn countries is export oriented. We must therefore, and it is absolutely essential, that we find a way to get this ban lifted. This is something that we are trying to help coordinate, and action is being taken by FAO, which is the agency that coordinates this with the humanitarian coordinators, and governments in the countries concerned, as well as the importing countries, primarily in the Gulf.

Question: I sense that the original question was too limiting and that there are other issues that concern your office.

Answer: Now, as for the future, one of the issues that we are also concentrating on is information. The data that is being collected in the countries of the Horn is very rich, and yet it is not collected on a consistent and uniform manner. There is no agreed system between those that collect data, so what comes in is not managed to allow a good picture to be available for action in time of crisis…neither is there a data bank for the region as a whole, that is reliable. We are building a "framework" for the countries of the Horn to help them standardize and improve their systems, with a view to extend the future data banks to a regional dimension. We will want to give attention to the key crisis areas, such as the pastoralists, without ignoring the very vulnerable agricultural areas. For the moment, we are very closely watching the belg rains in Ethiopia and similar short rainy seasons in other countries, which will determine what happens with the big harvest later in the year. The other points that we need to concentrate on are recovery and rehabilitation, a sort of bridge from emergency to sustainable livelihoods. We need to make sure that initiatives in the recovery and rehabilitation field are properly supported, that they make sense, and that they are coordinated properly so that you do not have disparate and contradictory projects in the same areas, in similar environments, with little planning. That brings me to a point that is perhaps the most important- the food security on a longer-term basis. There have been discussions on food security policies in Ethiopia, in Eritrea, in Kenya and certainly in Somalia, over many years. But, there isn’t yet a coherent policy in regard to the mix between what is emergency food needs and the chronic food deficit, which is more the result of poverty, lack of arable land, overpopulation and basically, underdevelopment. This is an issue that has to be faced first by the governments concerned, of course by the people, but the people have little control over policies that the Governments adopt. They cannot take the initiative on their own. We have to get Governments involved in further discussion and development of a food security policy that does not depend on food aid. Obviously, donors will have a very strong role in such discussions. They have of course also been already engaged in such discussions in Ethiopia, among other countries, but they have not made a breakthrough yet with the governments, as this is a complicated issue. What we would like to do is help all of the actors to come together and try to develop a food security policy on a mid and long term basis which takes account of future funding, including continuity of food aid pledges. The latter cannot be taken for granted. It is indeed, I repeat, a very complicated issue, but is a sector that the humanitarian community must tackle.

Question: What are some of the effects of food insecurity?

Answers: Nutrition, under-nutrition and malnutrition are issues that have plagued the Horn of Africa populations over the last twenty years and, centuries. There isn’t a policy, or methodology, or programme approach, to address this on global, or uniform, basis. It is all done in bits and pieces in different countries in different regions, at community level. We are still struggling with defining how to address malnutrition in rural areas particularly difficult to access and we have different methodologies of measuring malnutrition. This is something that is being discussed. There is a meeting in Nairobi later this month on this subject and we would like to profit from this initiative, so as to find ways of addressing the problems with NGOs and other UN system organizations, such as UNICEF and WHO.

Question: What about coordination within countries?

Answer: In each of the countries in the Horn, you have dozens perhaps hundreds of non-governmental organizations that work side by side with UN organizations, with governments and very often, in fact probably universally, there is insufficient coordination between them, despite frequent meetings. You would have either the same kind of initiative on development recovery or even addressing emergency needs done in a completely different way in one village in one region from another village in another region. Here in Ethiopia there are of course coordinating mechanisms: DPPC at central government level, DPPB at regional level. However, there doesn’t seem to be a coherent policy yet that would ensure that all of the actions, in the relief field, make global sense, that there is a policy that would lead to a development of durable assets, for the populations affected by calamities. So, you have initiatives, interventions that help people on a short-term basis, but what you need in order to address the issue of chronic poverty is to make sure that the people who are poor have additional assets created on an incremental basis so that in the future they will reach a minimum level of self-sufficiency. NGOs seem to be working very much on their own and their collaboration with the UN has been good, but can still be improved. We would like to make sure that they and the UN and humanitarian operators feel part of one group that addresses the same issues in a way that we can all understand, and agree on.

Question: Recognising the drought as a major issue to be dealt with by your office, are there other issues outside that scope that your office deals with?

Answer: Yes, we are including the issue of internally displaced persons (IDPs). The regional humanitarian office is meant to deal only with drought, but you cannot make a distinction between people displaced because of the drought and as a result of insecurity, e.g. during the clash between Eritrea and Ethiopia. There have been displacements of people on the northern frontier of Ethiopia and the southern frontier of Eritrea, and there has been displacement in the Somali frontier region over many years. There have always been movements of people between frontiers in countries like those in the Horn, and the issue of IDPs is a very serious subject for policy consideration for all the countries in the Region. We would like to make sure that we make a contribution to the resolution of that problem.

Question: Please allow me to shift attention to the role of your office in policy issues of pastoralism?

Answer: We have proposed as part of the appeal, a project proposal to the donors that relates to pastoral issues. It is a project that would create a future framework for development of policy on pastoralists, the way that communications with pastoralists should go forward- that is networking at the ground level- from the pastoralists to local structures, whether they be at village level, at regional level or at whatever administrative structure exists. This project was proposed as a relatively modest initiative. We have a donor that has, in principle, agreed to fund it. They have encouraged us to boost it and build it up into a bigger project. At the present stage, it has more than doubled in its original size. It is going to involve several experts with an office in Nairobi and specialists in Ethiopia and by the time we finish there may be other experts elsewhere. This is an initiative, which I think is valid for the problems of the Horn and hopefully it will build something that we can build upon further in the future. Pastoralists are a minority group in numbers; however, when it comes to the economy and territory they are important and their problems need to be addressed. So we think that this project is a catalyst for future action and with luck may lead to several new initiatives in the next few years. Hopefully it will be able to address some of the problematic areas that pastoralists have always faced.

The Prevailing Humanitarian Crisis in Somali Region

The UN Emergencies Unit for Ethiopia undertook a field trip to Jijiga, Hartesheik, Kebri Dehar, Fafen and Shinile from 13 to 18 February 2001. A full copy of the report is available on the UN-EUE web site at http://www.telecom.net.et/~undp-eue/2001_mnu.htm

Their observations illustrated that if one were to superimpose a photograph of Gode in January 1993 onto one taken in January 2000; it would likely be difficult to discern any difference. Some of the faces, in fact, would be the same. Likewise, the humanitarian and development communities in February 2001 are facing a situation much the same as the one they faced in February 1994. The field officers noted that the advantage we have this time is knowing that we failed rather miserably the first time in terms of preparing for the next drought. We also now know from this experience that simply going away is not a solution.

The mission report emphasizes that there are both immediate and long-term needs in the SNRS. Solutions in the immediate term are readily provided through the delivery of humanitarian assistance. Solutions for the longer-term, however, must come from the people of the Region and the Government. The Regional President has demonstrated willingness and ability to turn the fortunes of the Region around, to work closely with international organisations (UN, ICRC and NGOs) and to provide an administration that is responsive to the needs of the people. He is constrained, however, by the vastness of the Region and the distances one must cross when travelling from the capital Jijiga south to Degeh Bur, Warder, Kebri Dehar, Gode and Mustahil and south and west to Dolo and Moyale or directly west through Dire Dawa to Casbule in Shinile over roads that are mostly dirt and rock tracks (with the exception for the main road Jijiga - Dire Dawa). The telecommunications network is also extremely poor, and pales in comparison with nearly all other regions. With these conditions as a background, the administration is tasked with the daunting challenge of bringing into balance a complex clan structure with expectations at all levels for an appropriate share of rather limited resources.

On the positive side the SNRS is a region with unexploited resources and underdeveloped capacity. The people are straightforward and determined. The Region has survived a serious war fought on its soil and persevered through decades of limited development support and periods of humanitarian crisis.

Chronic Food Insecure Areas along Tekeze River and Simien Mountains

A mission was undertaken by the UN Emergencies Unit for Ethiopia (UN-EUE) from 10 to 17 February to remote areas difficult to access in the eastern parts of the Simien Mountains and in the Tekeze River lowlands. The objective was to obtain first hand information from farmers on general living conditions, and the agricultural and food security status. The mission compared the actual situation with what was encountered in two previous visits in 1999. A complete copy of the mission report will be available in a week by accessing the UN-EUE web site at http://www.telecom.net.et/~undp-eue/2001_mnu.htm

Basic infrastructure development under way

Since 1991, some basic development efforts have been undertaken in remote weredas around the Simien Mountains and in part of the Tekeze River watershed. For the last five years, especially Ibnat and Belessa weredas in South and North Gonder respectively, have received considerable attention and benefited from road construction programs, terracing and small-scale irrigation projects mostly carried out under food-for-work (FFW) development activities and employment generation schemes (EGS). In the remote highland weredas such as Jana Mora and Beyeda, basic infrastructure improvement started only very recently. Places such as Mekane Birhan are now accessible by car. Storage facilities have been built nearer to the beneficiaries and a suspension bridge made the remote Beyede wereda accessible. Many households are gaining income and are receiving additional food and cash resources through these state-supported and subsidised programmes. But apart from creating temporary employment opportunities for farm households, the sustainability of these measures is debatable.

Limited, unhealthy and ecologically harmful coping mechanisms

In most chronically food insecure areas of Amhara Region, on-farm crop production contributes only up to a maximum of 50% of the annual food requirements, even in good years. This is no surprise with average farm size of 1.5ha and an average soil productivity decline of 3% annually. Furthermore, the population density is well above the carrying capacity of the ecosystem. Today massive structural and agro-ecological deficits prevail which require drastic measures. Some of the few available and adopted coping mechanisms are unhealthy and ecologically harmful, such as cutting down indigenous tree species and consuming toxic crops in times of food shortage.

New trends and developments; state-subsidised food and cash allocations

In view of the manifold constraints people face in food insecure areas, for the time being there are not many viable opportunities to keep them off the food trap. Market opportunities will remain low and development potential will face serious structural constraints due to climatic, agro-ecological, bio-physical and environmental constraints. Too many people and animals live in an ecologically fragile environment that cannot sustain, support or feed the present numbers. Livestock, the only traded item besides indigenous wood and wild-food, is traded in Tigray. Markets are hundreds of kilometres away and water availability is very limited. River diversions and other small-scale water projects do not stand a chance of sustainability. For such projects, the water flow has to be guaranteed.

Government officials and development specialists alike agreed that indeed integrated food security is very difficult to achieve in certain chronic food insecure areas, when it comes to the question of sustainability. The only immediate option to keep these populations alive is to guarantee subsidised food and cash allocations for development activities through government with the help of the international donor community. In other words; the populations of these areas are kept busy and are able to survive through non-sustainable outside incentives. Obviously this cannot be the solution. In the mid- and long term, more drastic measures such as emigration and resettlement of parts of such endangered populations have to be considered.

Release of Final Report on UNAIDS/UNFPA

Joint Post-conflict Assessment on HIV/AIDS

As a response to resolution 1308, passed by the UN security council on 17 July 2000, a series of joint UN missions are being deployed to assess HIV epidemic factors in conflict, post conflict and peacekeeping situations. Accordingly, a UNAIDS/UNFPA mission was undertaken to Ethiopia and Eritrea from 23 October to 7 November 2000. The mission has now released its final report.

The report identified that the military, social and economic dynamics resulting from the conflict have had a disastrous effect on the HIV epidemic in Ethiopia, significantly increasing the spread of the virus even in the areas where prevalence was not previously high. The post-conflict period also presents a serious challenge. The redeployment and demobilization of troops back into their communities poses its own risks. The report noted the introduction of a peacekeeping mission with up to 5000 military troops and civilians being deployed in the border regions and the capitals of both countries, added to the already complicated situation. The troop contingents are from countries with widely varying HIV/AIDS policies and prevalence in their own military forces. They will be deployed in areas with many displaced and economically destitute people, particularly vulnerable women. As underlined by the report, some are educated about HIV prevention; others are not. Some receive condoms as a matter of course in their own militaries; others do not. Thus, these forces may both be at risk and present risks within the Ethiopian context.

Although a number of initiatives are being planned and considerable financial resources are available, the mission stressed that there is still insufficient awareness of the state of emergency posed by the lethal mix of troops, displacement, vulnerability, destruction of health services, lack of access to condoms and the imminent demobilization of tens of thousands of soldiers. In short, the report describes, the pieces of the puzzle are there in Ethiopia to fight the HIV/AIDS, but it will take concerted efforts by all stakeholders and active coordination to put those pieces together into an effective response to the crisis.

Integrated Methodologies for Landmine Clearance

Landmine contamination in Ethiopia has restricted access to many areas. In particular, along the border in Tigray and Afar regions many internally displaced persons that have returned now face the danger of landmines every day. Yet, few know the ins and outs of how a landmine is actually cleared.

Today, the field of demining aims to remove landmines more rapidly, more safely and in a more cost effective manner through the use of integrated methodologies. For instance, if a suspect area covered a hundred square kilometers, manual deminers could potentially be tied down on that single field for months or years. Therefore, the Ethiopian Mine Action Office is looking into other options for landmine clearance to complement their manual demining programmes. These demining options include:

Rapid Response Teams

Rapid Response Teams are designed to address the immediate need of communicating the danger of mines to the local population, to mark landmines and to remove/reduce any immediate threat. These teams would be deployed to contaminated areas where they can respond on short notice and conduct their function within the community. Teams, composed of various specialists, will not only assist in the mapping and disposal of mines/unexploded ordnances (UXOs), but will also provide mine awareness to the local population by explaining the danger of mines. They will gather information regarding the possible mined areas from the population and mark dangerous areas working in cooperation with local authorities. These teams would allow the removal of an immediate threat in a shorter period of time and lead to a decline in and prevention of casualties.

Mine Detection Dogs (MDD)

Dogs have a remarkable ability to locate landmines by detecting the odor of explosives in the mines. Dogs are trained to locate mines by isolating the specific scent of the explosives as well as the plastics and metals used to manufacture the mines. These scents permeate the mine casings and rise up through the ground into the air. Dogs, with the ability to smell about 1,000 times greater than humans, can detect this specific smell and zero in on the exact location of the explosive. However, dogs do not work alone, but operate with specially trained dog handlers who complete the MDD team. MDD teams work especially well together with manual deminers in areas where the mine-laying pattern is unknown. Manual deminers prepare an area by dividing it into boxes of 10 by 10 meters by clearing lanes one meter in width. During this action the deminers will remove the threat of tripwire mines. The MDD teams will then search the boxes for the presence of mines. If a dog indicates the presence of a mine in a box by sitting down close to the landmine, deminers will manually clear the box. Where a dog does not indicate anything in a box no further action in that box will be required. After the first dog searches the box, a second dog will double-check the same area. Dogs are more accurate and consistent than people, but can be negatively affected by wind and rain.

A well-trained MDD team can cover an area of 2,400 square meters minimum per day. In comparison, a manual demining team of eight members can only cover 500 square meters maximum per day. This makes the inclusion of MDD a cost-effective and productive option which could triple the speed of clearance/release of land.

Mechanical Systems

Mechanical systems are extremely effective in accelerating the progress of demining, especially for large areas that are suspected of mines. A wide range of machines is available on the market today such as flails, rollers and vegetation cutters. Although the machines can be very expensive, ranging up to several hundred thousand US dollars for large machines, they can be used cost effectively. These "tractor-like" machines are used to speed up the clearance process by preparing the ground for manual demining and to reduce the danger during manual clearance. They remove ground cover and turn over soil to expose and or explode any landmines. Machines are also very valuable to verify areas where the presence of mines are not confirmed but suspected. A large flail can cover up to 10,000 square meters per day.

On the downside, these machines cannot work on steep land and can have an environmental impact on the terrain being cleared. They remove vegetation and loosen the topsoil during flailing. Therefore, mechanical systems are best utilized only on terrain that will be cultivated in the near future or in limited impact procedures that effects only a small portion of the overall target area.

While machines and dogs can speed up the clearance process, mine action programmes will integrate manual demining with these methodologies to ensure compliance with 100% clearance standards.